Returning home after my last year of college, everything looked smaller and closer together. I had spent time in British Columbia, where everything seemed magnified, lusciously green, almost fantastical. And in Saskatchewan, the ashen fields ran to the distant sunsets in uniform sheets of golden gray. Now, as the train glided over the countryside, the barns, fence rows, corn cribs, and silos looked like a hand-carved village set up on a patchwork quilt of cornfields. The lands I had once roamed and known to the elm and the stone pile now seemed quaint and detached from the greater world. Mom assured me that this sort of disdain is common among young people who have moved away from small towns like ours. When I have children, indeed, I will look back wistfully at the countryside where I grew up and will move back to the farm on the north shore of Lake Erie.

Anyone who has experienced the intensity of summer in southwestern Ontario knows the suffocating humidity, the contradicting droughts, the thunderstorms racing across the night horizon. That summer I fled often to the lake, only a short bike ride to the south of our farm. Half a mile along the main drag out-peddling the barks of the friendly neighbourhood dogs. Take a right at the corner store and peddle hard and straight, coasting down into the gully and giving ‘er up the other side. Past the cornfields and off the highway onto the washed-out gravel hill. Finally I would leap off, as the tires hit the sand. Toss “Blue Boy” – the bike my father had bought me from a neighbour – onto a heap of natural debris: zebra muscles, sticks, seaweed; out of the way of the trickle of fishermen and sunbathers.

I would take off my sandals and then wade along the shoreline, picking out beautiful stones and polished pieces of glass. Then I’d crouch in the wet sand and allow the hypnotic cycle of waves to calm me. I would listen, watch, and later on my towel, write.

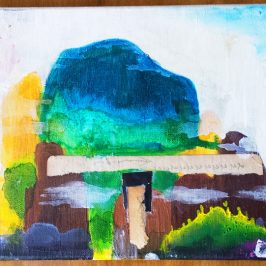

On a particular day, the sky was a mix of Payne’s gray and yellow ochre; a sleepy canopy of still, saturated air. It offered an occasional, restless rumbling that breathed hope of an evening thunderstorm. The banks curved out to the far left and far right of where I lay to the gently lapping water until they disappeared into the haze. Once in a while, the sun penetrated the thick air, adding energy to the already blistering sand. I took refuge in the shade of the tall sand hoodoos, carved into the bluffs by lonely winter winds and waves. On the water, a pair of terns cried and landed on a bobbing island, a wave softened log.

At some distance several parties moved about, passing in and out of the water, setting up umbrellas and chairs, fishing. A little girl chased a beach ball into the waves and fell over. Her father swooped in behind her and lifted her to her feet. It made me think of Dad.

It was harvest time. The large orange wagons were lined up along the headland of the front field. I traipsed along between two bleached rows of freshly combined soybean stubble, watching my rubber boots and singing. I didn’t hear Dad coming over the rattle of the tractor, his long strides diagonally cutting across the bean rows. “Hello, Pooh Bear,” he picked me up from behind and swung me halfway up the wagon so that I could reach the metal rungs. I eagerly climbed over the top and dropped into a sea of soybeans. The tiny pea-sized grains shifted and spilled dizzyingly into the valleys left by my footsteps. I bent over and started sifting them, burying my hands. Cool, smooth beans ran into the sleeves of my jacket and overflowed my rubber boots . . . The sky was blue and full of floating white islands. Kingdoms, I thought. That must be where God lives. But that was only a fleeting thought as I started swimming in my own enchanted sea of beans. . . .

I got up and walked along near the bluffs, hoping as always to discover a cave. This time, I had ventured farther down the shore than ever before, and I found a crevice in the bank, a meandering trail of packed ground that was obviously a dried up creek – that year was a drought. Our lawn was a lifeless beige. The corn was “firing.” Mom said if the firing crept up to the ear, it would be bad news. Crumbled flakes of clay lay along the edge of the fields, gaping cracks had formed on the back lane.

Dad always got quiet at this time of year. It was hard to read him – was he just quiet or depressed? It was frustrating to be a farmer now, with the price of crops so low. That was one thing I would give my farming kin credit for – they understood that farming was essential. People need to eat to live. But now dad had to work full time on top of farming to pay the bills.

I remembered back to the days before he had to work off the farm. One day dad had to take me to nursery school. I had finished watching Mr. Dress Up and was waiting at the porch window in my hand-me-down plaid pants and pigtails, holding my colouring bag. Outside I heard the rumble of dad’s tractor. Before it came into view, I could feel the sound in my chest. The door opened and dad picked me up and carried me to the red Massey Furgeson where he set me down behind his seat on a tough cushion, an island on the sea of greasy rags, wrenches, and pesticide leaflets. The tractor groaned and lurched forward down the bumpy gravel lane. It sang a lulling tune as we bumped along, and I started singing along, feeling its music in my throat. As we turned onto the smooth highway, the song raised an octave in pitch. I stared out the open space where there should have been a window at the dotted line down the centre of the road until it blurred into one yellow stream . . . like Little Black Sambo’s tigers.

Dad was a good father. At least not a bad one. Life on the farm is tough; he was frustrated by so many disappointments. Once that summer, I followed him at a distance after supper as he walked out to water the garden. I heard him ask God in desperation for just a few inches of rain.

Once in a while he would drive down to meet me on Lakeshore Road as I biked home from the park where I worked that summer, with the dog panting around the corner of the cab of the red pick-up. Then I would try to race the truck on Blue Boy down to the beach where he’d send the dog swimming to cool off.

I kicked around at the dry crick-bed the crumbled flakes of clay that lay near the beginning of the trees. Driftwood blocked the entrance. A good dollars-worth of beer bottles were scattered there in the shade; enough bare ground for a little tent. The only close sounds were the waves, the birds. In the distance, the hum of boats, voices. Was that thunder? No promise of rain. The lake was so warm that day that I could actually sit in it, sifting stones. “Picking,” my cultivated Toronto friend had said with disdain as I pored over The Beaches earlier that summer. But this day, I could enjoy everything; I was alone. Just me and Blue Boy. The evening Dad brought it home from the old man who lived in the brick house on the bend, I had appraised the dilapidated bike and asked if he really thought it was worth the twenty-five dollars. He lifted it it out of the back of the little red truck and wheeled it over. “It’s a good bike, like they used to make ‘em,” he announced. “These are called balloon tires, you know.” As I wheeled Blue Boy out of the sand toward home, I checked to make sure the spiderweb was still there. The bike had come with that spiderweb on the handlebars. I kept it; it was part of the bike.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.